Preamble 1: This is written to Christians, and intended as a call to my fellow believers in Christ to hold to very high standards of truth telling, particularly as it relates to the COVID-19 pandemic we are currently facing. I do think that the general principles I am espousing here apply to others as well, and all our welcome to read and comment.

Preamble 2: In this post I do talk quite a bit about holistic healing/alternative medicine. This is an area of complexity and nuance, but here I am primarily talking about self-proclaimed alternative health “experts”: modern day snake-oil salesmen who are seeking to use the COVID-19 crisis to create a name for themselves and garner greater fame and fortune. I know many of my friends lean towards ‘holistic’ alternatives or adjuncts to modern evidence-based medicine (modern medicine IS holistic but that’s another soap box entirely). I have FB and real life friends who are into essential oils, I have family that swear by their chiropractor, and I myself have received acupuncture in the past (it was kind of fun, to be honest). Most of them, thankfully, also choose to bring their children to the doctor when they are ill and to vaccinate them to prevent communicable diseases. Most of them have been very, very supportive of healthcare professionals in general and of me personally during this pandemic, and I have seen them both seek out and share good, reliable medical information. In short, I have been quite proud of these crunchy, oily friends of mine. If you are reading this as someone who identifies strongly with holistic or alternative medicine, I would ask you to please consider carefully whether the conspiracy theorists and COVID-19 deniers who are so prolific on the internet right now really represent your movement well and are espousing the same values that you find important in your area of wellness. My hope is that you wouldn’t be deceived by them easily just because they are comfortable using the same terminology that you hold close to your heart; an error we in the Church have all too often made with false teachers of all stripes.

“Finally, brothers and sisters, whatever is true, whatever is noble, whatever is right, whatever is pure, whatever is lovely, whatever is admirable—if anything is excellent or praiseworthy—think about such things.”

“Keep your tongue from evil, and your lips from telling lies.”

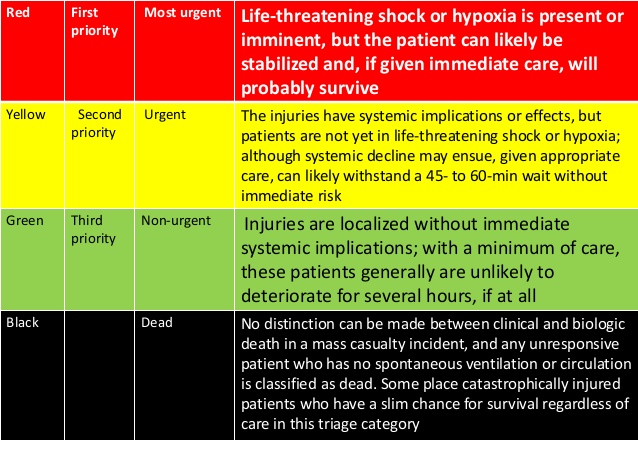

When the initial wave of concern over COVID-19 began for our clinic system a few short weeks ago, there seemed no end to the things that needed to be done. We had to rapidly prepare to protect our staff and patients by minimizing transmission risk and eliminating fomites, go through all of our processes with a fine toothed comb and revise or rewrite a fair number, and innovate and implement novel ways to deliver high quality primary care under circumstances where it was no longer safe for our patients to sit in a crowded waiting room as they wait to see their primary care Physician, or even pass each other in the hallways on the way to the lab or radiology. This all in addition to learning how to work-up and treat the virus itself. During those first few weeks many of us worked until the wee hours of the morning each night and through the weekends, all the while continuing to see patients, return phone calls, and refill medications. But as these systems have been put into place and fine-tuned, and as the physical distancing and other epidemiology measures on a community level have effectively limited the spread of the virus in our area, life has thankfully slowed somewhat again. Many of us that do hospital work are waiting to see whether more doctors will be needed to cover shifts, or if the shelter-in-place orders and distancing measures will be enough to avoid a true, overwhelming surge. In the meantime we read and stay up to date, we see our patients via telemedicine or in outdoor COVID-19 clinics and work hard to make sure they don’t fall through the cracks, and we prepare, personally and professionally, for worst-case scenarios. Throughout all of this we have each continued to ask ourselves what our next responsibility is as Physicians in the midst of this pandemic.

In answer to that last question, I have found myself more and more called on to provide an answer to misinformation around COVID-19, as friends and family have attempted to sort out the unprecedented amount of misunderstanding and abject falsehood that has been circulated over the past month. To be clear, even in the best of times there is already an overwhelming amount of misinformation around health and healthcare. The nuances of human health and disease and the means available to protect the former and fight the latter are unbelievably complex, and because of this it is easy for an individual who hasn’t spent a lifetime studying this area to feel overwhelmed and disempowered. The temptation of easy answers and quick fixes is very real. More to the point, Physicians have historically done a fairly poor job, in my opinion, of helping our patients to feel empowered and knowledgeable to the greatest degree that is possible without them actually entering the medical field themselves. In this context, it is no surprise that during this time of increased health anxiety and uncertainty, and with a myriad of political and economic motivations to obscure the realities around the virus, the amount of misinformation has increased dramatically. Between my day job, extra duties related to the virus, and this small matter of having a wife and four children, I consider it a real privilege when I have the margin to address a video or article that a friend has ‘tagged’ me in asking for my input.

But though there are plenty of unaddressed articles, videos, and memes spreading medical misinformation on my facebook feed this very day, I am writing this afternoon with a slightly different, though related, purpose. I am writing to call the Church to participate in this work with me.

We are called to be a people of the truth; we are not called to be a people of truth and falsehood mingled. When discussing his conversion to Christianity, G.K. Chesterton wrote, “My reason for accepting the religion and not merely the scattered and secular truths out of the religion… I do it because the thing has not merely told this truth or that truth, but has revealed itself as a truth-telling thing.” As followers of Christ, Christians ought also to have a reputation of truth-telling. Truth-telling in love, when the truths are difficult. Truth-telling in courage, when the the truths are spoken to those in places of power. Truth-telling in humility and repentance when those truths reflect poorly on ourselves or our conduct. We cannot afford the damage done to the witness of the Church by our gaining a reputation as unreliable sources of truth. Yes, physical health in general and the COVID-19 pandemic in particular, as devastating as it is, are still ultimately minor issues compared to the eternal importance of the Gospel; but how can the world around us look to us for the Truth of the latter when we have only provided them falsehood about the former? “Whoever can be trusted with very little can also be trusted with much, and whoever is dishonest with very little will also be dishonest with much.”

For this reason, I believe that our willingness as a people of Faith to perpetuate misinformation, particularly when it may truly injure our neighbors, is not a political issue or even an integrity issue, but a spiritual issue. There is no truth, whether philosophical, metaphysical, or scientific, that does not belong to our Creator; there is no Truth that we as Christians should fear, and there is no falsehood, no matter how convenient to our preferred narratives, that does not originate from our Enemy.

What follows is my take, as a Physician, on what a lay person can do when trying to weigh truth and falsehood and judge the reliability of medical information during the COVID-19 pandemic. I want you to know that I realize it is often very, very difficult. As a Physician I have the privilege of years of education and training in thinking about real and reliable truths about our bodies and the diseases that affect us; it is never my place to judge someone for sharing information they find convincing because they do not have those same experiences and have spent their time in other important work. It is my job, I think, to help my fellow believers supplement their God-given discernment with reliable data and professional insight; we are all one Body, but made up of many parts.

1. Understand your source.

Returning to Chesterton, I think it is reasonable to ask whether the author of the article or the self-purported expert we are listening to has a track record of providing reliable medical information; have they proven themselves to be a ‘truth-telling thing (er, person)’. Many of the people generating widely shared false information are political partisans who have no medical or other scientific background; are they sharing the perspective of actual experts, or are they merely creating false narratives and opinions out of thin air? If the source is not a politician but instead claims to be an expert, what is their education and background? So often we give our trust to people whose primary credentials are an attractive and disarming physical presence and a high verbal IQ but who do not have even the basic science background to understand the frameworks they are tearing down. I have seen youtube videos captioned ‘so and so DESTROYS the COVID-19 pandemic myth’ or ‘Dr. X crushes the CDC and WHO conspiracy’, etc., only to find that not a single intelligible sentence of valid scientific information was uttered during the entire 15 minute video. These are the ‘used car salesmen’ (no offense to actual used car salesmen; I am very pleased with my 2012 Honda Odyssey) of medical information, and their true area of expertise is in pretending to be experts.

Please understand what I am not saying; I am not saying that you must have a certain degree or a certain prerequisite combination of education or work experience in order to have a valid take on the pandemic. But often these videos are made by people putting themselves forward as experts without the credentials to support that claim; the first piece of misinformation is imbedded in their own self presentation. An example is a video a friend recently asked for input on, from a doctor putting himself forward as an expert on the immune system. It turns out that he was not an immunologist or a microbiologist, but a disgraced chiropractor turned “cellular detox diet” specialist. Again, this does not negate what he has to say; but it is a vital piece of context for weighing the claims he goes on to make.

This research is sometimes hard. These people are often incredible at building legitimate sounding resumes for themselves and at using terminology on their websites and bios that smacks of authenticity and scientific rigor. Moreover, there are also those who do have impressive credentials yet have strayed from any integrity in their work and have become deeply unreliable sources of healthcare information in their pursuit of fame or fortune (a fellow MD friend and I often joke, darkly, how easy it would be to make tons of money as a Physician, if it weren’t for these pesky morals). But even if you cannot establish someone’s reliability with a few minutes on google alone, conducting such research will help to answer a few basic questions that should set the tone for the information itself. Is there a direct link between the reach of this person’s social media influence and their opportunities for attainment of power and profit, such as a political office being at stake or a website that sells services or goods directly? Such a relationship would be fairly rare in medicine or academic science. Are the claims this person makes the types of things that would fall within their area of knowledge based on their education and work experience? Are they setting themselves up as experts in areas, such as clinical medicine, immunology, or epidemiology, where they seem to have had little to no experience? Finally, do they have a history of fraudulent claims, moral turpitude, or failed (or successful) scams in the past?

This step is sometimes a bit tedious, but I believe vitally important, especially when some of these videos are made by people who have spent a lifetime mastering the art of convincing others with their looks, manners, and likability. When it comes to medical misinformation, these are the wolves in sheep’s’ clothing of the moment.

2. Do your research.

This second point is so similar to the first that I won’t spent much time on it. Though understanding whether the source is reliable is important, I firmly believe that the content of the argument is more important still. When considering any degree of medical information shared on social media, or even mainstream media, pause to reflect on the main themes and content of the article or video. What was the driving point? What information contradicts that which is already widely available? What data seems shocking or seems to rely heavily on the existence of widespread conspiracies? For that matter, do those conspiracies depend on the sudden cooperation of diverse and often opposed sectors of society, such as the sudden cooperation of politically unaligned nations or the widespread collusion of large groups of healthcare professionals? What part of the information is benign and widely accepted already, and is it being presented as such? Or is there a claim that commonly accepted facts are denied by or unknown to ‘the powers that be’ (the CDC, the medical establishment, etc), and does that seem very likely? What would the major implications be if this video were true, and who would stand to profit by its widespread acceptance if it were false?

This list could go on, and in another time we would have only these important critical thinking questions to guide us to the informational content itself. But we live in a technological age and the odds are that if we are seeing a video, or at least a popular video, it has been critiqued or fact checked already. Read these critiques; seek them out. This alternative perspective, even if it comes from a source you normally don’t subscribe to personally (I know people who despise certain fact checking websites), may be enough to give you the ‘aha!’ moment you need to reach conclusions on the information for yourself. And if you believe the information and think it is worth sharing, then understanding the arguments against it will only strengthen your position.

3. Be honest with yourself about your political leanings.

I’ll keep this one brief because I don’t particularly want to be dragged into a specific political debate, at least at this time. As people of faith who are committed to the truth, we will find ourselves politically homeless a fair amount of the time, and holding onto important caveats and a sense of tension even in our areas of agreement with political movements. When the truth conflicts with the narratives of the political groups with which we most closely align, our choice is clear. Before sharing information from questionable sources, that our research tells us is not reliable, we have to check our politics; we have to be very honest with ourselves regarding whether our impulse to perpetuate the information stems from a real belief in its veracity or from a mere desire for it to be true. I have heard fellow Christians tell me “all politicians lie” (generally to excuse untruths from one group or individual), and then have seen them blindly re-post the lies that come from their own side. I may very well have been guilty of this myself. If we believe that politicians are not reliable sources of information in general (and we can debate later if some are worse than others to an almost unprecedented degree), it means that we will sometimes choose for reasons of discernment not to pass along information that, were it true, would be extremely convenient to our party or candidate. In contrast, if we find ourselves always repeating the party line and reinforcing the narratives of those in positions of power, I fear that we are in danger of rendering unto Caesar something that never belonged to him.

4. Beware of easy answers.

“Reality, in fact, is usually something you could not have guessed. That is one of the reasons I believe Christianity. It is a religion you could not have guessed. If it offered us just the kind of universe we had always expected, I should feel we were making it up. But, in fact, it is not the sort of thing anyone would have made up. It has just that queer twist about it that real things have. So let us leave behind all these boys’ philosophies–these over simple answers. The problem is not simple and the answer is not going to be simple either.”

C.S. Lewis wrote this when discussing the reality of Christianity and the complaint heard so often that ‘religion ought to be simple.’ But I think this quote is informative for us in this discussion of medical misinformation. Alternative health popularizers like the ones we are seeing in video after video right now have long mastered the art of combining oversimplified ‘common sense’ arguments with the right kind of complex medical vocabulary (some real, some fake), to appeal at once to both our desire that healthcare should be fully comprehensible and explicable to us and our desire to know we are hearing form an expert. They are experts in tickling the ears, in confirming our biases and ingratiating themselves to a public that is anxious over health and disease. For someone who has actually studied both the real concepts they are distorting and the real vocabulary they are misusing, these arguments are as transparent as they are ridiculous; but they are not trying to convince me, they are specifically trying to convince people who don’t have medical training.

That said, you don’t have to spend your life studying pathophysiology and be intimately familiar with medical terminology to spot these patterns for yourself and know when to be wary. These false arguments tend to fall along a few common themes, and once you learn to spot them you will be a big step closer to at least being able to ask the right questions.

- The real solution is easy but they don’t want you to know that.

This one has come up a lot recently as people advocating against social/physical distancing measures (for political or financial purposes) are pushing the idea that other simple measures would actually prevent getting sick from COVID-19. Typically these are oriented around the immune system, and the idea that having a healthy immune system would actually prevent the disease entirely. Aside from being untrue, this is extremely problematic for two big reasons. First, I think we should recognize the degree of victim blaming involved in this line of reasoning; if these 41,000 people who have died from COVID-19 in the US had just taken enough Vitamin C or eaten a healthier diet they wouldn’t have died. Certainly the interaction between health and lifestyle, including limitations in choices and socio-economic vulnerabilities, is complex. But there is not a set of choices that can make someone immune to illness in general, and in the case of infectious diseases specifically there is not a combination of lifestyle and nutrition that can make a person invincible (even Chris Trager got the Flu on Parks and Rec). Second, just consider the sheer number of people who would have to be in on such a conspiracy. Millions of doctors, nurses, and public health experts, many of whom have themselves become ill or lost friends and loved ones. The idea that all of these people are interested in covering up that a certain number of milligrams of Vitamin C or a certain number of hours of sunlight exposure could have alleviated all of this suffering is not only incredibly naive, but also unbelievably calloused.

This is an argument that crops up when discussing any infectious disease, but it is particularly popular now. Many alternative health and particularly detox and microbiome style wellness salesmen are all too quick to tell you that viruses, bacteria, and fungi are important for us; that without them we wouldn’t have functioning immune systems. And they are right. But like so many of their arguments, they have taken just one piece of the incredibly complex story of human health and disease and have extrapolated it to illogical and harmful proportions. I have written about this more extensively recently, but they are essentially failing to make two important points. First, the difference between a microbe (any bacteria, virus, or fungi, etc) and a pathogen, which is a microbe known to cause human disease; it is absolutely not true that because ‘germs are good for us’, therefore infectious diseases are good for us. This virus can definitely kill you. And second, the role of an acute infection in establishing a secondary immune response. Yes, exposure to a pathogen does generally cause some degree of enhanced natural immunity against that same pathogen later (this is the entire principal upon which vaccines are based); but it is not necessary to allow yourself to get ill or indeed become as sick as possible in order to build that robust secondary immune response, and sometimes the risk is much greater than the reward. “Whatever doesn’t kill you makes you stronger” still implies that dying is at least on the table.

I won’t rehash all the points I wrote about last week, but instead will share a quick story. When we lived in Denver we were visiting with a friend after church who showed us a fairly deep cut to his finger, near the joint, which he had received that morning. My wife, an RN, asked what he had used to clean the wound. He explained that he had NOT cleaned the wound because his body needed the germs to build an immune response, and that soap and water would prevent his body from fighting off the infection ‘naturally’. Katie attempted to persuade him otherwise and explain the roll of his immune system and ways he could help his body prevent an infection, but he wasn’t convinced. Two weeks later we saw him again, this time with a large bandage over his finger. We asked about this and he explained how his finger had become infected and he had to go to the emergency room, undergo and incision and drainage procedure to remove the pus, and then take antibiotics. He went into glorious detail about the procedure and the appearance of the infection and even showed us pictures. He did all of this without any sign of chagrin, and to this day neither of us is sure whether he had forgotten the first conversation entirely or if he is just the world’s most humble man.

And while what happened to my friend is funny in retrospect, because his finger fully recovered, it is certainly not funny when someone contracts a deadly illness because they are misled into thinking it’s actually better for their health.

- The doctors don’t understand (or indeed know about) the immune system.

I’m always amazed when this one makes the rounds because it’s just such an incredibly goofy thing to say. We could spend paragraphs discussing the thousands of hours spent in medical school understanding every aspect of the human body and the huge swaths of microbiology, biochemistry, pathophysiology, infectious disease, anatomy, and pharmacology coursework that were devoted to understanding our fearfully and wonderfully made defenses against infection. I promise you we spent so much time studying the immune system that we dreamed of angry macrophages and inflammatory cytokines. So why such a silly and nonsensical lie? They are setting up a false dichotomy between your own immune system (which they would like to sell you products and services to augment) and the “big-pharma model of medicine”, a red herring of their own invention, which only believes in harsh chemicals. They have to reduce modern medicine and the scientific discoveries of the human body to just this one aspect in people’s minds so that they can claim for themselves the parts of it which seem to sell best. Whether the hucksters making such claims have actually studied the immune system in an intellectually honest and scientifically rigorous way themselves, however, is a question that perfectly justifies speculation.

I explore the rest further in the next section, but a few more, briefly:

- The doctors want you to stay sick.

This is 100% a lie. Don’t be fooled by ‘common sense’ arguments that suddenly call for millions of well-meaning people to act nefariously.

- The doctors are being controlled by big pharma.

Don’t be fooled by arguments that require passionate, notoriously difficult to control, and (let’s face it) often egoistic people to suddenly be submissive. Physicians are one of the primary reasons that pharmaceutical and insurance companies don’t yet control all of healthcare.

- The doctors mean well but have been tricked.

Don’t be fooled by arguments that require very smart people to suddenly be easy to dupe.

5. Ask your brothers and sisters in Christ.

One of the many false narratives that Christians seem to believe at an alarming rate is that the medical field is somehow opposed to the Church. It is easy to point to controversial areas of medicine, or even the general principles of understanding illness and health as primarily physical phenomenon, to say that modern medicine is at it’s core agnostic or secular, and thus antagonistic to the Faith. This is an incredibly profitable narrative for televangelists and healing charlatans who would like you to believe that pursuing any means of healing aside from the overtly miraculous is a sign of lack of faith, and who exploit our fears and insecurities around health to sew mistrust in Physicians and other health professionals for their own profit. Perhaps a step down from the overt chicanery of these false prophets, we also see a strange marriage between Evangelical Christianity and unproven and sometimes even dangerous alternative health measures, which are marketed, sometimes, with a heavy mix of pseudo-Christian spirituality.

But if this is true, what then do we do with the millions of doctors, nurses, scientists, epidemiologists, and others within the healthcare sector that are faithful followers of Jesus Christ? I think the first temptation, too often, is to treat them like they are ‘one of the good ones’; as though a Christian Physician you know personally may be a reliable source of health information, but the medical field, in general, is not. I think this is incredibly problematic. As someone whose 20’s and 30’s were devoted to medical training, I have known hundreds (maybe thousands) of doctors personally. My older children who grew up during my residency thought that “Dr.” was just a gender-neutral way to say “Mr.” or “Mrs.”. Because of where I have trained, many of these have been believers; but just as many that I have trusted and respected have not. Yes, I have certainly met doctors I would not trust with my own care or that of my family, but these have been remarkably, surprisingly few compared to the number of doctors I have known and worked with. In general I can say that Physicians as a group have self-selected for (and certainly this has been reinforced by training) both their desire to see people well and their commitment to scientific accuracy. To be clear, some of these doctors I disagree with vehemently on issues within medicine and the associated underlying moral and societal values. Nevertheless, and regardless of the cultural misrepresentations, your doctor wants you to be healthy and is, in general, a good and reliable source of information about health and disease. If they aren’t, you should get a new doctor immediately.

As we touched on earlier, a second and similar way to treat Christian Physicians and healthcare workers is as well-meaning but ultimately misled pseudo-experts with only a narrow scope of understanding regarding the human body. This is the view pushed by many in alternative health businesses; doctors are generally altruistic or noble, but they have had the wool pulled over their eyes, their education is controlled by Big Pharma and hospital administrators, and really all they are learning is essentially spreadsheet after spreadsheet of ‘if the patient has this, give them one of these drugs (and here are the prices; pick the most expensive one)’. Medical schools and residencies exist to train doctors to create profits for drug companies. Now, this is an incredibly silly idea and we could devote as much time as we wanted to this. I could explain that I never met a drug rep until after residency, because they generally aren’t allowed to interact with medical students or residents, and have never made a medical decision based on the advice of a drug rep in my life (except for Burton “Gus” Guster, of course). I could (and should, at some point) explain the very complex and often antagonistic relationship between systems within medicine that prioritize profits over people, including pharmaceutical companies, and the physicians, nurses, and clinical staff who exhaust themselves to help their patients find something like justice and equity in their healthcare. But these are areas I am passionate about, and I’m afraid this one section would eclipse the rest of the essay entirely.

Instead, I’m willing to bet that if took a step back and consulted even your own experiences with doctors you know personally, you would realize that their knowledge, education, and personal characteristics does not seem to match this narrative. If you have physicians in your family,, or in your church or Sunday school class, or have attended high school or college with them, or have friends who are doctors- in short, if you do know believing medical experts that you would ask for input on these videos and articles being circulated- ask yourself if they are a reliable source of information even aside from their medical background. Are they the type of people who are easily duped? Do they hold to questionable morals or a low view of the truth? Do they seem to possess discernment? Essentially, are they the type of people you would trust outside of a pandemic to answer questions unrelated to viruses and immunology and epidemiological data? If they are not, I would humbly suggest that you do not turn to them now, regardless of how closely the information you need clarified matches their field of work. But if they are, I would recommend showing them the courtesy to believe that they have applied at least that same degree of critical and independent thinking and that same spiritual discernment to the endeavor that has taken up the majority of their adult lives; namely the study of human health and disease.

Finally, my advice when framing these questions: be specific. When I am asked by a friend or acquaintance to address a viral video or a healthcare related article or meme, I try to be as thorough and complete as possible (I do find that after a few thousand words of my ramblings, they usually don’t ask a second time…). This can be time consuming, but I believe it is important work, and I personally have no problem being asked a general “would you give your input on this.” Not all healthcare professionals have the inclination to be quite so verbose, and of course many of us want for the time to do so now more than ever. If you ask for an opinion on a 20 minute video or a 2000 word article, let them know what your specific question is, or what about the content you found either particularly compelling, surprising, or questionable. If you are only looking for a ‘yes this is trustworthy’ or ‘no this isn’t trustworthy’ and are willing to take their word for it without a long explanation, let them know that as well.

6. Repent (or at least, redact).

I hesitate to make this last point because there is no way to express this without sounding somewhat judgmental. I hope it is clear that I intend to hold myself to this same standard as well, and hope that when (not if) I also fall into the ‘fake news’ trap and share misleading or unreliable information, I have the courage to follow my own advice.

What do you do when you have found information available on the internet and outside of your own area of expertise to be convincing and have passed it along, and through the (hopefully) kind input of friends have later discovered it to be untrue? I think there are a few good options. The simplest is to take it down; to delete the post so that others will not either follow you into believing the false information, or else in disbelieving it themselves begin to associate you with it. I think this is the minimum standard we should expect regarding our interactions with falsehood. However, I think an even better idea is what I have seen a family member do consistently in recent years; whenever she has shared a fake article or untrue information, she has then edited her post to clarify that the information is not reliable and why. Rather than distancing herself from those mistakes she embraces them, and in doing so helps protect others against the same errors. I believe that even better than Christians being known for never spreading false information (which is surely not the case now) would be us being known for the integrity and humility to publicly repent of error and embrace truth; in fact I can think of no more Christian way to deal with such a situation.

There is one thing we cannot do. Once we are aware of the falsehoods in something we have shared or promoted, we cannot choose to cling to it because we like the way it sounds or want people to believe that it is true. I have seen this done far too often; when it has been shown clearly that a source is unreliable or has even told outright lies, I have seen friends choose to continue to endorse and share it. There are myriad reasons, from liking a few of the points that weren’t exactly dishonest to wanting people to accept the overall message even if the content isn’t reliable. As people who believe that truth is authored by our Father and that we have an enemy who is only the father of lies, we cannot be comfortable with the mingling of the two. We cannot say, “yes, 7 of his 12 points were deliberately dishonest, and maybe or 3 or 4 were fairly dangers, but I really liked the other 5 and he’s just such an engaging speaker.” We must hold to higher standards of veracity than this. If we really want to promote those other ideas we should be incredibly, unmistakably clear that the rest of the content is not trustworthy… But better still, we should do the difficult work of finding a more consistently reliable source, and say of the first only that “he is a liar and the truth is not in him.”

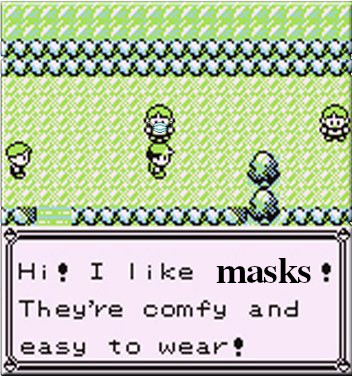

I will conclude with the words of our Lord from Matthew 10:16: “Behold, I send you out as sheep in the midst of wolves. Therefore be wise as serpents and harmless as doves.” This pandemic is unlike anything we have seen in our lifetimes, and it is already the number one cause of death in the United States. We are living in an era of human history when reliable, true information is really capable of saving lives and when false information endangers our friends, loved ones, and neighbors. As we seek to obey the command of our Savior, let us reflect that we may never again in our lifetimes see such a moment as this, when these two concepts are so closely linked and refusal to be as wise as serpents can lead so directly to a failure to be as harmless as doves.